Updating the Arecibo message for 2025

In 1974, a group of scientists broadcast a message towards Globular Cluster Messier 13 with the Arecibo telescope. The message was crafted in such a way that any aliens receiving it would potentially be able to understand some basic information about humanity. However, it contains some information that we now know to be inaccurate. What would the modern version look like?

The components

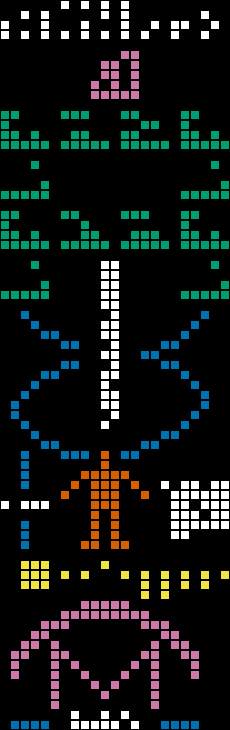

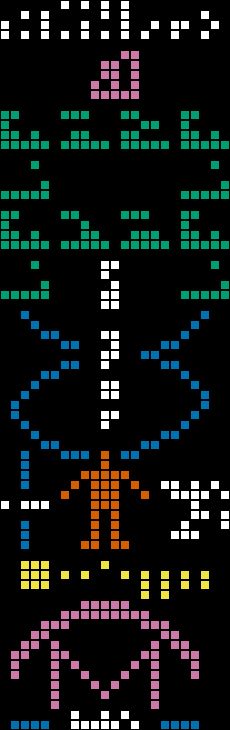

The wikipedia article is great and goes into detail about how the components are meant to be interpreted, but I'll briefly summarize their purpose here (from top to bottom, with colors matching the image):

1. The numbers one through ten

2. Chemical elements in DNA

3. DNA backbone with two base pairs

4. The estimated number of base pairs in the human genome

5. A picture of a double helix

6. (left) A ruler to indicate the human's height

7. (left) The number 14 (when multiplied by the wavelength of the message, it gives the height of the average human male)

8. (center) A picture of a human

9. (right) The estimated population of humans in 1974

10. The major bodies of the solar system, with Earth raised

11. A picture of the telescope

12. Unclear - maybe this indicates the ground?

13. The number 2,430 (when multiplied by the wavelength, it gives the diameter of the telescope)

The problem

The technology of the time made it impossible to accurately measure the number of base pairs in the human genome, and the value they used turns out to have overestimated it by over 37%. It was also coincidentally extremely close to the then-estimated population, which I can only imagine would send our alien interlocutors down a rabbit hole. The full human reference genome sequence was (perhaps surprisingly) only finally determined in August 2023 (see this nice overview that covers how the reference genome has improved over the last few decades).

Updating the Arecibo message

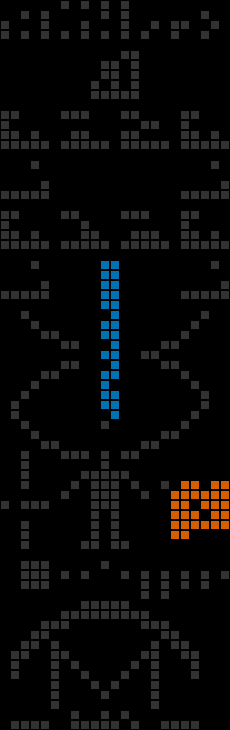

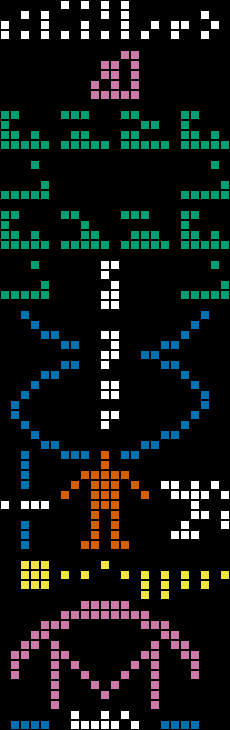

I wrote a CLI tool to generate the message with user-provided values for the genome size as well as the population, which has obviously changed. On the left, I've highlighted the components being updated (blue is the genome size, red is the population), and on the right, we see the message if it were being sent today, with 3,117,275,501 base pairs and 8,098,171,861 humans (the estimated population by the US Census at the time of this writing):

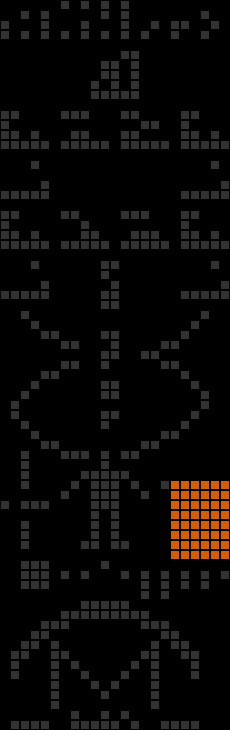

Buffer overflows and Pluto

The human population is represented by a binary number read from left to right, top to bottom, with the least-significant digit coming first. The largest value this could ever hold (see image on the left) without expanding into the depiction of the solar system would be 281,474,976,710,655 (unless we destroy every planet after Jupiter, which would give us an additional five rows of six bits, for a total of 302,231,454,903,657,293,676,543) - either way, we'll be able to continue using this format to alert aliens to our presence for many years to come. To accommodate the transition that occurred in 2006, the CLI tool also has a --pluto-is-not-a-planet flag that disables Pluto (right).

The CLI

Install: cargo install modern-arecibo

Repo: https://github.com/jimrybarski/modern-arecibo

Crate: https://crates.io/crates/modern-arecibo

My experience using mutation testing in production

What is mutation testing?

Mutation testing is a technique for improving the correctness of your software, answering the question: do my unit tests actually cover every branch of my code? Mutation testing tools are external programs that make syntactically-legal alterations to your codebase, run your test suite (which is left unaltered), and check whether any of your tests fail. Effectively, it's like deliberately adding bugs to your code in a systematic way and seeing if you're already testing for those bugs (and, of course, reverting the bugs after testing is complete). For example, take this toy function:

def filter_records(records):

for record in records:

if record.quality < 30:

continue

yield record

The mutation testing library will flip the < to >, yield record to yield None, 30 to a bunch of different numbers, and so forth. It's mostly limited to operators, strings, and constants, and the details vary by tool and language. Only one of these so-called mutants is tested at a time - while it would be possible to create multiple mutants for a single test run, practical experience shows that this doesn't add much value, and the run time would explode exponentially.

If none of your tests fail even after adding these "bugs", it shows that your tests are incomplete - adding bugs should cause failing tests! Your job is then to either write more unit tests or refactor such that the things being mutated cease to exist. This is complementary to code coverage tools, which can only show whether a line was executed during the run of a test suite. It's still possible - likely even - that you can have 100% line coverage while still missing some behavior. Take this example:

if x and y:

launch_rocket()

if z:

load_cargo_onto_rocket()

Suppose you have one test where x and y evaluate to True but z is False, and another test where x or y is False and z is True. In one test, launch_rocket() will run, in the other, load_cargo_onto_rocket() will run, but you still haven't exercised the scenario where x, y, and z are all True, which would reveal that this code is going to launch an empty rocket and then try to load cargo into a vehicle that is no longer there. A test coverage tool will correctly inform you that all four lines are tested, but the most critical behavior is ignored.

My experience with mutmut

I had a greenfield project at work and I decided it was a great opportunity to give mutation testing a whirl. This was for a Python application that, in broad terms, took raw sequencing data and determined the error rate of an enzyme. I looked at Cosmic Ray, Mutatest, and mutmut. I ended up choosing mutmut as it just seemed the most polished at the time. I never did any rigorous comparison so I don't want to endorse it over the others, but I was mostly pleased with it.

Overall, I'm super happy with mutation testing, but not because it caught many bugs. In fact, I think it really only found 1 or 2 true positives, and they were relatively minor. The real benefit was that it deeply impacted the design of the codebase such that it was the most testable piece of software I've ever written. This happened because each time I added some new feature, I had to immediately consider whether I wanted to write dozens of unit tests to eliminate the mutants, or whether I wanted to refactor in a way that made it easier to test. Having a bunch of new mutants show up is often a sign of unnecessary complexity.

Towards the end of the project, I had been thinking that it was probably not worth it to test the main entrypoint function in the tool as I'd need to essentially simulate an entire run of the application starting from raw sequencing data, but as I was so close I decided to spend a few hours writing it, and I'm glad I did. Having the entire codebase killing all its mutants not only gave me confidence that the code was correct, I could also fearlessly make changes.

mutmut has a few flaws

Some mutation testing tools do everything without altering the source on disk - the code is loaded, altered and tested in memory (which is apparently possible!). Because each mutant is independent of every other, this is embarrassingly parallelizable. mutmut, on the other hand, writes each change to disk and then runs the test suite, one mutant at a time. This is certainly a much simpler design, but in addition to being slower, if you cancel the run partway through, the mutant that was being tested at the time will persist on disk! This isn't an issue if you committed your source just before the run since it would make reverting it trivial, but I typically want to see if my tests pass before I commit, so I had to sift through all of the deliberate changes I had made in order to find a single-character alteration.

Advice on adopting mutation testing

- Fast test suites are essential

If you can run your entire test suite in one second, and you have 300 mutants to test, then adding mutmut to your workflow means it now takes five minutes to run your tests. There are a couple things you can do to optimize this, fortunately.

First, the key is to observe that the vast majority of the time, mutants will in fact cause tests to fail, so you want to optimize for failing fast. If you have any property-based tests or slow-running tests in general, you can configure pytest to run them last by marking them as slow. Often, mutants will be killed by several different tests, so if you can kill them with fast tests, you can shave off meaningful amounts of time.

Second, while a bit obvious, is to not run mutmut until you're ready to commit, or only run in CI. Since it will identify a number of false positives in any new code, any time spent resolving those is wasted if you end up changing your design. I found that just running unit tests while developing, and then only running property-based and mutation tests once I thought I had something worthwhile ended up being a good compromise. The iteration time on finding out if I had architectural flaws was still fast enough that I never had to do any major refactors.

- Start early

After my initial success, I tried bolting on mutation testing to an existing project and it was a nightmare - there were hundreds of surviving mutants, and resolving them would require several refactors and just tons and tons of work that I simply couldn't justify. Having the tool constrain the design from the start really is critical. It's not impossible to adopt it later, but it does require a non-trivial investment.

- Skip plotting functions and other "untestable" code, but here there be dragons

mutmut works on an opt-in basis, so it will only modify files you explicitly tell it to. My tool generated a bunch of figures with matplotlib, which is not practically testable, and for those functions I just kept them in a separate module. I do have the habit of doing some light data wrangling in such code (e.g. something like getting all the values from a dictionary and plotting a histogram, instead of just passing in a list of values directly). Although it's trivial, "this can't possibly be wrong" is the thing that everyone writing a bug is telling themselves, so I tried to move as much of that code as possible to the modules where mutmut could evaluate them.

- Mutation testing tools are still somewhat limited

Only being able to modify operators, strings, and constants is powerful but doesn't provide complete coverage. Notably lacking from all of the tools I looked at is the ability to alter method calls. For example, they can't remove .strip() from a string variable, or swap .is_upper() with .is_lower(). To do so would require type inference, and the libraries for doing that in Python don't seem like they could easily integrate with a mutation testing tool, if they would even work at all. I have high hopes for Ruff, which is implementing a type inference engine, and once that matures I think there would be a great opportunity to merge that into existing tools or to design one around it. Until then, it's still a great technique, but it's important to recognize this limitation.

- Mutation testing won't catch all bugs

While the combination of unit tests, property-based tests and mutation tests did basically result in functions that were all correct (I mean, as far as I could tell), I still encountered a bug that was more strategic in error. In essence, I had told my tool to do the Wrong Thing, and then had tests that ensured the Wrong Thing was being done exactly as instructed. This kind of error will never be caught by any of these techniques, so we'll always need a human or human-level intelligence to review the code and think critically about it.

Some initial thoughts on developing Lua plugins for Neovim

I wrote a bioinformatics Neovim plugin recently. It's nothing super special - it just provides some sequence manipulation functionality like generating or searching for a reverse complement, performing a pairwise alignment, etc. It really surprised me how often I found myself using it in day-to-day work right after I installed it.

This was my first Lua codebase and it definitely left me underwhelmed with the language. I mean, it's fine - it's a very small language and you can get proficient pretty quickly. First-class functions are easy and it feels like you're being guided by the language towards using them. But overall, it just feels unpolished and I simply don't understand the enthusiasm for it. Some issues I had:

- The only compound data type is a table (an associative array) that returns

nilwhen unmapped keys are accessed. So more or less the same API asdefaultdictin Python. This can make debugging a nightmare, as a typo in a field name wherenilis an expected value makes it seem like the value just never gets set. Maybe this is less of a problem with experience, but it's a completely unforced error. Other languages simply don't have this problem because they have data types that make this error impossible. - Variables are scoped globally by default, with opt-in local scoping. I just can't imagine a scenario where this is preferable.

- The lack of a built-in unit testing framework is disappointing. I had trouble getting Vusted (a tool for unit testing Neovim plugins) installed because I didn't run the installer as root. What is the deal with modern language-specific package managers requiring root (thinking of the node ecosystem in particular here)? My only guess is that this is easier for people who don't understand how to set their shell's path and this is a strategy for not discouraging less-experienced programmers. But that sort of person is just copying-and-pasting anyway, and you can just do what Rustup does: add something to their .bashrc and print a little note about how they need to restart their terminal to be able to immediately use their new program.

- The

vimobject in Neovim plugins can't be accessed by an LSP, so you're unable to view or reference the internal Neovim API, and it just appears to the LSP like an undefined variable. It's possible to disable those lints on a per-variable basis, but this is still pretty suboptimal. There does seem to be plugin for this so maybe this is just growing pains. - Unintuitive naming for built-in functions, like

#variable_nameto get the length of a string orgsub()to do replacement. What does that "g" stand for? It might be "global", but I haven't found a source for this that wasn't just speculation.

That said, once you figure out the idioms and boilerplate, plugin development becomes super easy. The language provides so few abstractions that there's really only one way to do anything, which I appreciate.

DS9 viewing guide

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine is one of my favorite shows, but the quality of episodes is all over the place, especially in the first two seasons. I made this list so that people I recommend the show to can skip the bad episodes and also follow the longer-term story arcs. Episodes colored in yellow have important implications for subsequent episodes, introduce a new character, or change the nature of some important relationship. This currently only goes through season 5, I will add to this over time.

| Season | Episode | Title | Rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | Emissary, Part 1 | Fine | Series debut. Some context: the reason Sisko doesn’t like Picard is because in an episode of TNG, Picard was kidnapped by cyborgs (the Borg), turned into a cyborg, and he became their leader and went on a killing spree (which killed Sisko’s wife) before ultimately being saved and reverted to a human |

| 1 | 2 | Emissary, Part 2 | Fine | |

| 1 | 3 | Past Prologue | Fine | Introduces Garak, the best character |

| 1 | 4 | A Man Alone | Meh | |

| 1 | 5 | Babel | Meh | |

| 1 | 6 | Captive Pursuit | Meh | |

| 1 | 7 | Q-Less | Skip | The only Q episode, which just grates against the entire theme of the show (even more so than in TNG) |

| 1 | 8 | Dax | Fine | Explains the Trill species |

| 1 | 9 | The Passenger | Meh | |

| 1 | 10 | Move Along Home | Unwatchable | |

| 1 | 11 | The Nagus | Poor | |

| 1 | 12 | Vortex | Meh | Changeling backstory |

| 1 | 13 | Battle Lines | Fine | Ehrmantraut from Breaking Bad in space |

| 1 | 14 | The Storyteller | Unwatchable | |

| 1 | 15 | Progress | Fine | Occupation worldbuilding. The old man is a bit much |

| 1 | 16 | If Wishes Were Horses | Unwatchable | |

| 1 | 17 | The Forsaken | Very meh | Mostly bad, but has a sweet ending. |

| 1 | 18 | Dramatis Personae | Skip | |

| 1 | 19 | Duet | Excellent | Incredible performances, great story |

| 1 | 20 | In the Hands of the Prophets | Meh | |

| 2 | 1 | The Homecoming | Good | |

| 2 | 2 | The Circle | Fine | |

| 2 | 3 | The Siege | Good | |

| 2 | 4 | Invasive Procedures | Frustrating | I would skip because a character does something really unforgiveable and it’s better to think of this as non-canon. The rest of the characters certainly do |

| 2 | 5 | Cardassians | Great | Garak absolutely annihilates this episode |

| 2 | 6 | Melora | Bad | |

| 2 | 7 | Rules of Acquisition | Very meh | The Ferengi go to the Gamma Quadrant. Some important foreshadowing but nothing critical happens. |

| 2 | 8 | Necessary Evil | Decent | |

| 2 | 9 | Second Sight | Bad | |

| 2 | 10 | Sanctuary | Bad | |

| 2 | 11 | Rivals | Bad | |

| 2 | 12 | The Alternate | Meh | |

| 2 | 13 | Armageddon Game | Decent | O’Brien must suffer |

| 2 | 14 | Whispers | Good | O’Brien must suffer |

| 2 | 15 | Paradise | Fine | O’Brien must suffer |

| 2 | 16 | Shadowplay | Fine | |

| 2 | 17 | Playing God | Meh | Trill background |

| 2 | 18 | Profit and Loss | Fine | |

| 2 | 19 | Blood Oath | Fine | A scene in this episode is often referenced by trans rights activists |

| 2 | 20 | The Maquis, Part 1 | Decent | Wikipedia: Maquis (World War II) |

| 2 | 21 | The Maquis, Part 2 | Decent | |

| 2 | 22 | The Wire | Good | Iconic Garak episode. His philosophy on the truth had a big effect on me. |

| 2 | 23 | Crossover | Skip | I personally hate Mirror Universe episodes |

| 2 | 24 | The Collaborator | Good | |

| 2 | 25 | Tribunal | Fine | O’Brien must suffer |

| 2 | 26 | The Jem’Hadar | Decent | Nog is very annoying but it’s otherwise a good episode |

| 3 | 1 | The Search, Part 1 | Good | Scepter |

| 3 | 2 | The Search, Part 2 | Good | |

| 3 | 3 | The House of Quark | Fine, goofy | Some great moments, but you have to buy into the ridiculousness of Klingon culture to enjoy this |

| 3 | 4 | Equilibrium | Meh | |

| 3 | 5 | Second Skin | Decent | Garak |

| 3 | 6 | The Abandoned | Fine | Quark makes a hilarious purchase |

| 3 | 7 | Civil Defense | Good | |

| 3 | 8 | Meridian | Meh | |

| 3 | 9 | Defiant | Good | I’m not actually that into these episodes, but here is a quote from Wikipedia about it: “as this episode was finishing production an article appeared in the Los Angeles Times describing a proposal by the mayor to create fenced-in "havens" for the city's homeless, to make downtown Los Angeles more desirable for business. The cast and crew were shocked that this was essentially the same scenario that Past Tense warned might happen in three decades, but was now being seriously proposed in the present." |

| 3 | 10 | Fascination | Bad | |

| 3 | 11 | Past Tense, Part 1 | Meh | |

| 3 | 12 | Past Tense, Part 2 | Meh | |

| 3 | 13 | Life Support | Fine | |

| 3 | 14 | Heart of Stone | Mixed | A story: bad, B story: great |

| 3 | 15 | Destiny | Fine | |

| 3 | 16 | Prophet Motive | Meh | |

| 3 | 17 | Visionary | Good | O’Brien must suffer |

| 3 | 18 | Distant Voices | Bad | |

| 3 | 19 | Through the Looking Glass | Skip | Mirror Universe episode |

| 3 | 20 | Improbable Cause | Good | |

| 3 | 21 | The Die is Cast | Good | |

| 3 | 22 | Explorers | Meh | |

| 3 | 23 | Family Business | Bad | Two recurring characters are introduced, but man this episode has some bad takes |

| 3 | 24 | Shakaar | Fine | |

| 3 | 25 | Facets | Mixed | A story is lame, B story with Nog is decent |

| 3 | 26 | The Adversary | Good | |

| 4 | 1 | The Way of the Warrior, Part 1 | Good | |

| 4 | 2 | The Way of the Warrior, Part 2 | Good | |

| 4 | 3 | The Visitor | Good | |

| 4 | 4 | Hippocratic Oath | Good | In case you forgot this was made in the 90s, the episode opens with a very unfortunate gay panic |

| 4 | 5 | Indiscretion | Decent | |

| 4 | 6 | Rejoined | Decent | Gay rights allegory in space. “Hippocratic Oath” must have had a completely different production team |

| 4 | 7 | Starship Down | Decent | |

| 4 | 8 | Little Green Men | Fine, goofy | |

| 4 | 9 | The Sword of Kahless | Fine | |

| 4 | 10 | Our Man Bashir | Good, extremely goofy | Garak’s emphatic defense of cowardice left a big impression on me as a youth |

| 4 | 11 | Homefront | Decent | This episode aired almost six years before 9/11 |

| 4 | 12 | Paradise Lost | Decent | |

| 4 | 13 | Crossfire | Meh | Odo becomes an incel |

| 4 | 14 | Return to Grace | Fine | |

| 4 | 15 | Sons of Mogh | Decent | |

| 4 | 16 | Bar Association | Decent | “He was more than a hero - he was a union man!” |

| 4 | 17 | Accession | Fine | I think this is the episode that introduces the weird way that Bajorans clap. They clap weird. Look at their hands when they clap. |

| 4 | 18 | Rules of Engagement | Decent | |

| 4 | 19 | Hard Time | Good | The epitome of the “O’Brien must suffer” episodes |

| 4 | 20 | Shattered Mirror | Skip | Mirror Universe episode |

| 4 | 21 | The Muse | Bad | |

| 4 | 22 | For the Cause | Good | |

| 4 | 23 | To the Death | Good | |

| 4 | 24 | The Quickening | Decent | |

| 4 | 25 | Body Parts | Decent | |

| 4 | 26 | Broken Link | Good | |

| 5 | 1 | Apocalypse Rising | Good | |

| 5 | 2 | The Ship | Good | |

| 5 | 3 | Looking for par'Mach in All the Wrong Places | Fine | |

| 5 | 4 | ...Nor the Battle to the Strong | Good | You’d think this title was a Bible quote, but nope |

| 5 | 5 | The Assignment | Good | O’Brien must suffer. Nana Visitor (who plays Kira Narys) was written out of this episode as she went into labor on set. Alexander Siddig (Julian Bashir) was the father. |

| 5 | 6 | Trials and Tribble-ations | Goofy fun | Basically one continuous reference to a famous Original Series episode |

| 5 | 7 | Let He Who Is Without Sin… | Bad | |

| 5 | 8 | Things Past | Meh | Odo occupation backstory |

| 5 | 9 | The Ascent | Decent | |

| 5 | 10 | Rapture | Decent | |

| 5 | 11 | The Darkness and the Light | Decent | |

| 5 | 12 | The Begotten | Meh | |

| 5 | 13 | For the Uniform | Decent | |

| 5 | 14 | In Purgatory’s Shadow | Good | Garak’s trolling of Worf was another formative interaction |

| 5 | 15 | By Inferno’s Light | Great | |

| 5 | 16 | Dr. Bashir, I Presume? | Fine | |

| 5 | 17 | A Simple Investigation | Bad | Odo loses his virginity but somehow remains an incel |

| 5 | 18 | Business as Usual | Decent | |

| 5 | 19 | Ties of Blood and Water | Decent | References a character from S3E05 “Second Skin” |

| 5 | 20 | Ferengi Love Songs | Meh | Quark and Rom have to decide if misogyny is good or bad |

| 5 | 21 | Soldiers of the Empire | Meh | They do Martok’s character dirty here. He’s so much better in every other episode he’s in. It is also revealed that the infirmary has carpet that’s difficult to get blood out of. |

| 5 | 22 | Children of Time | Good | |

| 5 | 23 | Blaze of Glory | Decent | |

| 5 | 24 | Empok Nor | Good | |

| 5 | 25 | In the Cards | Goofy, meh | |

| 5 | 26 | Call to Arms | Good |